History of Haiti: An Overview

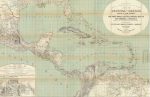

Before 1492: Prior to the arrival of the Europeans in the 15th century, it was inhabited by the Arawak and other indigenous peoples, the most dominant of which were the Taino and the Ciboney. The Taino, who were believed to number some half a million when the Europeans arrived, called the island Quisqueya.

December 1492: Christopher Columbus landed on the north coast and claimed the island for Spain, calling it ‘La Isla Española’, later anglicised as Hispaniola. Gold was discovered in eastern Hispaniola and the Taino were enslaved by the Spaniards to work in the mines. By 1508, as a result of ill-treatment, malnutrition and infectious diseases brought by the Europeans, the Taino population had been reduced to some 60,000 and in 1548 there were reportedly fewer than 500 left.

1570: The Spanish Crown authorized the importing of slaves from Africa. The few remaining Taino fled to the mountains and established independent settlements. By this time, gold reserves had dwindled and the Spaniards had moved on to Mexico and Peru in their search for mineral wealth, leaving Hispaniola prey to raids from French and British pirates. The western part eventually became settled by French buccaneers.

1697: Through the Treaty of Rijswijk, Spain ceded the western part of the island to France and what is now Haiti became known as Saint-Domingue. By the end of the 18th century, thanks to African slave labour, it became a highly profitable colony for France, exporting coffee, indigo, cocoa, cotton and, in particular, sugar.

1789: The estimated population of Saint-Domingue was by this time 556,000, including some 500,000 African slaves, 32,000 European colonists, and 24,000 affranchis (free mulattoes [people of mixed African and European descent] or blacks).

1791: Inspired by the French revolution, a major slave revolt spread through the north of the country. In December 1791, former slave Toussaint Louverture took command of the slave army.

1793: The British invaded Saint-Domingue.

1794: The new French Republic abolished slavery and Toussaint Louverture joined forces with the French to expel the British. Toussaint became Lieutenant-General of the colony. Under him, Saint-Domingue remained an authoritarian and highly-militarized state.

1799: Napoleon Bonaparte took power in France.

1802: After creating a separatist constitution, Toussaint Louverture was kidnapped by Bonaparte’s force and taken to France, where he was imprisoned and died in 1803.

18 November 1803: Touissant’s leading General, Jean- Jacques Dessalines defeats Napoleon’s forces decisively at the Battle of Vertieres. Cap-Haitien surrenders and the French commanders flee.

1 January 1804: Dessalines proclaims the country independent in Gonaives, renaming it Haiti (Ayiti in Haitian Kreyol), a Taino name for the island. But no European state or the United Sates recognise the new country.

September 1804: Following Napoleon’s lead in France, Dessalines proclaims himself Emperor in September 1804.

October 17 1806: Dessalines is assassinated. His death sparks a civil war between the black north led by Henri Cristophe and the mulatto south led by General Alexandre Petion. The country formally splits.

December 1815: Simon Bolivar arrives in Haiti after failing to find support in Jamaica for his efforts to free what are today Venezuela and Colombia from Spanish colonial rule. President Pétion agrees to support him on two conditions: he recognises Haiti as an independent nation and frees all slaves when his enterprise succeeds.

March 1816: Bolivar sets sail for South America with six schooners, a sloop, 250 men, mostly officers, and arms for 6000 men. After a few successful battles Bolivar begins to free slaves but faces a revolt from plantation owners and eventually his own men, a factor in forcing him to flee back to Haiti again the following year.

1817: Bolivar sails from Haiti again and is eventually successful in South America but fails to fulfil both commitments to his Haitian sponsors. As part of efforts to gain acceptance in the international community of nations he never recognised Haiti diplomatically and refused to invite the country to the first Congress of the American States held in Panama in 1826.

1821: Jean-Pierre Boyer, who has succeeded Pétion as President of the southern part in 1818, reunifies the country. When, shortly afterwards, the western part of Hispaniola, then known as Santo Domingo and at that time still a Spanish colony, declared its independence from Spain, Boyer sent in forces to seize control and continue to rule the whole island until ousted in 1843.

1825: With warships off the coast, France demands Haiti compensate it for its capital loss – principally its slaves — in the ceding of its colony. France agrees to accept compensation of 150 million gold francs in exchange for the recognition of Haiti. Even though this sum is eventually reduced to 90 million gold francs, by 1900 Haiti was spending 80% of its national budget on repayments. The debt was not finally paid off until 1947, 122 years later, much of the repayment financed by new loans from Germany, the United States and even France itself.

1844: The Haitians were expelled from Santo Domingo following a popular uprising.

1843 – 1915: During this profoundly unstable period, Haiti had 22 presidents, only one of whom completed his term of office. The country was effectively controlled by a small urban elite, made up of Catholic, French-speaking, light-skinned mulattoes, while the rural majority, made up of black, Haitian (Kreyol)-speakers who practiced Vodou or Roman Catholicism or a mixture of the two, continued to live in abject poverty.

1915 – 1934: Following increasing unrest and the mounting influence of the French and German communities in the country, the US Government used the murder of then President Guillaume Sam by an angry mob as a pretext for occupying Haiti. A treaty was signed with the United States establishing US financial and political domination.

1919: A peasant uprising against the occupation saw the establishment of a provisional government in the north headed by resistance leader Charlemagne Péralte. However, he was captured and killed some months later.

1934 – 1946: Although the US occupation ended in 1934, the country was still effectively controlled by the US through the local mulatto elite.

1946 – 1950: Amid increased economic hardship and political discontent, influenced by the ‘black power’ ideas of the noiristes, black ex-teacher Dumarsais Estimé was elected President with the support of the army and the left.

1950 – 1956: Dumarsais was deposed by Colonel Paul Magloire who, though professing to be the ‘apostle of national unity’, favoured the old mulatto elite. He in turn was forced into exile in December 1956, giving way to nine months of political chaos during which there were five provisional governments.

September 1957: In Haiti’s first election with universal adult suffrage, albeit controlled by the army, noiriste François Duvalier, a doctor and former minister in Estimé’s government who became known as ‘Papa Doc’, was elected President.

1957 – 1971: This period was characterized by extreme repression. Wary of the power of the army and political groups, ‘Papa Doc’ set up his own militia known as Tontons Macoutes, later renamed the Volontaires de sécurité nationale (VSN), who ruthlessly snuffed out any potential opposition.

1964: François Duvalier established a dictatorship, declaring himself ‘President for Life’.

1964: François Duvalier established a dictatorship, declaring himself ‘President for Life’.

1971: Death of François Duvalier. Prior to his death, he designated his 19-year-old son, Jean-Claude, known as ‘Baby Doc’, as his successor and also ‘President for Life’. Repression continued but not with the same degree of violence.

1986: Following increasing popular opposition, Jean-Claude Duvalier and his family fled to France. A provisional National Council of Government (Conseil national de gouvernement, CNG) was installed, headed by Army Chief of Staff General Henri Namphy.

Further reading:

- Haiti, Family Business, Latin America Bureau 1985

- Comment – Haiti, CIIR, 1988

- Haiti, Building Democracy, CIIR, 1996

- History of Haiti, Wikipedia

- Timeline: Haiti , BBC

- Haiti, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- The Haitian Revolution, Four-part essay by Bob Corbett, 1991

Marie-Louise Christophe Blue Plaque Unveiling Ceremony

Marking the unveiling of a blue plaque dedicated to Marie-Louise Christophe, first and last Queen of Haiti, at her former

Urgent Appeal for Queen Marie-Louise Christophe Plaque: A Heritage Crowdfunding Project by Fanm Rebèl

Together with the Haitian Chamber of Commerce, Dr Nicole Willson, based at the Institute for Black Atlantic Research, is raising

Haiti’s revolutionary and intellectual history has lessons for the future

This article first appeared in The Conversation and is written by our HSG Exec Member Dr Rachel Douglas. Original text

Press Release: Jovenel Moïse Assassination and Emergency Meeting

Press Release: Jovenel Moïse AssassinationThursday 8th July, 2021. The Haiti Support Group is shocked and saddened to learn of the

BREAKING NEWS: President Moïse Assassinated at Private Residence

It is with deep sadness and a heavy heart here at the Haiti Support Group to confirm today that President

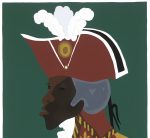

A revolutionary legacy: Haiti and Toussaint Louverture

The British Museum, in association with the The Asahi Shimbun newspaper, presents: A revolutionary legacy: Haiti and Toussaint Louverture. This temporary spotlight display

UPDATE: Donald Trump and Haiti. Help us shut his comments down

UPDATE, 12th January 2018: Today marks eight years after the Léogâne Earthquake and Trump is, once again, spewing garbage about Haiti

80 Years On: Revisiting the Massacre

This article originally appeared on NPR on October 7, 2017. The piece was written by Marlon Bishop and Tatiana Fernández. You

Fighting for Freedom

The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) heralded the beginning of the end of slavery in the Western Hemisphere, and the overthrow of